Have mercy on me, O God, according to your loving-kindness;

in your great compassion blot out my offenses. —Psalm 51:1

Ash Wednesday, the beginning of the liturgical season of Lent is second only

to Good Friday as  the most sober, and sobering, day of the Christian year.

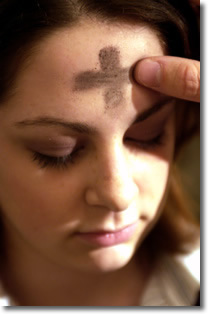

Believers across the globe go to church where, if you choose, you may

participate in what is called the Imposition of Ashes.The priest dips her finger into a bowl of burnt ashes, makes the sign of the cross on your forehead and says, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return."

the most sober, and sobering, day of the Christian year.

Believers across the globe go to church where, if you choose, you may

participate in what is called the Imposition of Ashes.The priest dips her finger into a bowl of burnt ashes, makes the sign of the cross on your forehead and says, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return."

It is not a day for the faint-hearted or for those who live removed from reality. For years, I was tremendously comforted by the thought that God knew me, loved me, and accepted me, but I did not give equal attention to the other side of the equation—the need to face my darker nature, name it, and seek forgiveness. I didn’t realize how naïve, even arrogant, I was being.

One Ash Wednesday, as I knelt in church, I saw how I’d been fooling myself. It was not a blinding light experience; I did not fall weeping before the priest. But I did connect the words of confession and penitence with the reality of my life, and I hope I will never be the same again. Now I approach the Ash Wednesday Liturgy with something like anticipation. It is oddly comforting to confess my sins and ask for strength to change.

Ash Wednesday is a good day. It offers a chance to join the eloquent psalmist who knew himself well and offered himself, sins and all, into the hands of a loving God.

Almighty God, in your great compassion, blot out my offenses and renew a right spirit within me. Amen. —Margaret Jones

Yet even now, says the LORD, return to me with all your heart,

with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning; rend your hearts and not

your

clothing. Return to the LORD, your God, for he is gracious

and merciful,

slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and

relents from

punishing.

—Joel

2.12-13

Today

is Ash Wednesday, the beginning of the

season of Lent. This season marks a

time of forty days set aside

for introspection and reflection. As this

passage from the

prophet Joel demonstrates, messages about Lent are

multi-faceted.

We are called to fast, weep,

and mourn, and

yet, we are asked not to tear our clothes as signs of mourning,

but to

tear open our hearts. Joel reminds me that even as God is

gracious and merciful, abounding in steadfast love, and relenting in

punishment,

so I must be gracious and merciful to myself. Being

slow to anger with

myself means that I will be less afraid to open up

my heart and to look

inside. Today, may I lovingly rend my heart

and look inside to see more

clearly where I need mending.

—Katherine

Bush

Ashes remind us, with a shock, that we are God's creation,

made for God, and not the other way around. Ashes remind us of the brevity of the gift of life, and

the grace of eternal life in the heart of God. Ashes remind us that we

are born

to live, really live, before we die. Ashes remind us of

a resolve to a

Lent, and a lifetime, of a more authentic relationship

with Jesus the Christ.

For reasons like these it does not occur to us

that we participate in a

"strange" custom of ashes and dust. To the

contrary. With hearts full of awe, we

seek gold and God in the

dust. —Douglass

M. Bailey

My own life and the lives of those I have come to know and love have convinced me that God is always being shown to us. Whether in public places or when we're alone, God can be seen in the familiar and the ordinary, in the strange and the unusual. We see this even in the recognizable Lenten themes of fasting and prayer, of confession and repentance, of forgiveness and reconciliation. These themes are a sacred plea, a prayerful cry from the human heart to God in which we say: “O God, please show yourself to our souls.” Our plea to have God shown to us is not a quest of simply ‘knowing,’ nor is it a need for proof of God’s existence. Rather, it is a desire for an awakening with God that will purify us, cleanse us, and make us whole by saving us from ourselves. When God is shown to our souls we are made complete in our hope in God, a hope that is eternal.

The divine appearance—God’s own showing—is not merely a symbolic or an imaginative appearance. It is a very real awareness of God that leads to an invitation to place our focus more on God and less on ourselves; to give ourselves to God rather than to the things that we possess or those things that possess us. Whenever God is shown to us, we are confronted by ourselves. We learn or realize something about ourselves as we discover the truth about God. Almost always, a certain kind of turning and bending on our part is needed, because we so often follow our own path and find ourselves far away from God.

But God follows us; God’s

holiness is shown to our souls and we are refreshed. Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent, is a

unique time for revisiting the work of the soul and taking stock of

what God has

done and is doing in us. It is a time for

letting go of those things

that possess us and lay a claim instead to our own

hope in Christ.

It offers us the opportunity to stop and bend backward, to

reflect and turn towards God. It reminds each of us that we can turn

and be made

whole in Jesus. For in Christ, God is shown more perfectly

to our souls. This

Ash Wednesday, and throughout Lent, may we see and

be made whole in

God. —Renee

Miller

Returning to dust implies that we've been dust before. Has that occurred to you? It reminds me of the big bang. I like the idea that we are all minor confederations of stardust. The universe has all the matter and anti-matter it has had from the alpha point and will have to the omega point. It's just being reorganized all the time. I find this awesome to contemplate.

There was a silly romantic comedy by Woody Allen, who is quite a philosophical theologian in his own right. I can't remember the title, but there's a scene I'll never forget. It was both hilarious and profound. He's always the main character, of course. In this scene, his elderly parents had died and their bodies had been cremated. He was at the funeral parlor for their memorial services, when the urns containing their ashes were spilled out in a slapstick accident. As they swirled in mid-air, they spontaneously reconstituted themselves into particulate clouds resembling the people they had once been and proceeded to do a song and dance routine celebrating love and life. It was the Woody Allen version of Ezekiel's dry bones.

Ezekiel says bones sing to us.I hear dust and ashes singing too, songs of our past and those who have gone before, songs of our future and those who will come after, songs of our essential kinship with all matter. My parents' bodies were cremated and mostly dispersed, although some of their ashes were interred in a marked place. But the dispersion helps me to feel them airborne all around us, making us laugh at their song and dance routine. It helps me to imagine them riding the winds of the upper atmosphere in celebration.

It's hard to contemplate dust and ashes without having the images of the explosions of the Challenger, the World Trade Center towers, and the Columbia flash across my frontal lobe. They were almost instantaneous transformations of so many precious life forms, along with such masterpieces of human artifice and artifact, blown back into their more elemental and particulate nature. The dust and ashes of those lost are singing of human striving, of enterprise and excellence, of aesthetics.

Presently we face the threat of violence that could blow us all to smithereens, making me wonder what this cosmic adventure is all about. Is it about the celebration of life in all its forms, in song and dance, artifice and artifact? Is it about blowing each other to kingdom come? And if it's about celebration rather than conflagration, then how are we to redirect ourselves, our energies, our arts and efforts?In the continual evolutionary reconstitution of particles, is there another way for protoplasm to self-organize, so that various confederations of dust could learn to coexist and maybe even cooperate in the service of the celebration itself? —Katherine Lehman

In her book Speaking of Sin, The Lost Language of Salvation,

Barbara

Brown Taylor talks about sin not as a list of

specifics, but as

different for

everyone. The trick is to

identify sin for yourself, to

really know yourself.

To do

this, Taylor says, look for the experience

that makes part of you die.

..

Ash Wednesday is the gateway to Lent. We have forty precious days to open ourselves up most particularly to God, to examine ourselves in the presence of one who created us, knows us, and loves us. We have forty days to face ourselves and learn to not be afraid of our sinfulness. We ARE dust, and to dust we shall return, but with God’s grace we can learn to live this life more fully, embracing our sinfulness, allowing God to transform us.

May God grant us: the wisdom to know ourselves; the courage to admit our sins; and the grace to receive God’s never-failing mercy and forgiveness. Amen. — Margaret Jones